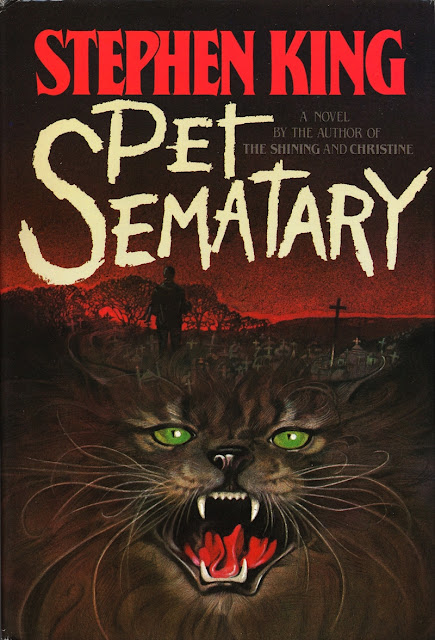

With the calendar having past the holidays of family celebration, I thought what better family oriented subject to take a peek at than Stephen King’s Pet Sematary. Okay, there are probably a few, but we’re here now and it’s worth looking at. Now, this isn’t going to be an overarching look at the entirety of the novel, nor will it be a comparison between literary work and film adaptation – at least, not completely. We are simply going to look at the main aspect of the novel, the same way I did in the second half of my Halloween piece. So, what makes Pet Sematary, one of King’s best and my favourite of his, work so well? Before I jump in to that, let's see where and how the story first got started.

Pet Sematary began life when King went to teach for a year at the University of Maine at Orono in 1978, the university being his alma mater. To do so, he moved his family into a rented home that happened to be by an incredibly busy street, which had claimed the lives of a few of the neighborhood children’s pets. The Kings themselves lost their cat to the road, and once one of his children had a close call themselves, King sat down and started work on what would become Pet Sematary.

He worked on it until he felt he had gone too far, his wife Tabitha and author-friend Peter Straub agreeing and disliking the novel, prompting him to put it away. So what ended up being the reason it got published to begin with? Well, he was in a contract where he was still obligated to hand the publisher’s one more novel. Tabitha recommended pulling out Pet Sematary, and King agreed. It’s interesting to think how close we may have come to not getting the novel at all.

For those that aren’t familiar, the novel follows a man named Louis Creed, a doctor, moving his wife, Rachel, and two kids, Gage and Ellie, to Ludlow main, with their cat, Church, as well. Their home is, of course, by a very busy highway. The children in the town that have lost pets to it have set up their own pet cemetery past the Creed's house. Losing Church to a truck, the neighbor that Louis had become friends with, Jud, shows him a place past the pet cemetery and the woods, a place said to be a Micmac burial ground. Having been buried there, Church does indeed return, though not quite himself. He smells bad after a while, as if he is rotting, and he begins killing small animals and tearing them apart for fun, not eating them at all. Things are made more complicated once two-year old Gage is hit by a truck and dies, and Louis decides to bury him…

I’m glossing over a bit, but the important points are there. Good horror comes from many places. Great horror, most times, comes from connecting its overall horror oriented aspects with real world and life. This can be done in multiple ways. It can, of course, be symbolic, such as what I wrote about Michael Myers previously. But the most effective horror uses its overall horror-ness as a way to explore us, and the human condition. For example, Shirley Jackson’s fantastic Haunting of Hill House and the effects of isolation within this house on the main character through her own insecurities. It’s why Carrie works, to pull from King’s bibliography, and it’s why Pet Sematary works.

It also has an important distinguishing factor in terms of how people try to write their characters actions. A lot of the time, people try to put their characters through certain events that rely fully on what they do and expecting our sympathies to still lie with them. This isn’t always done well, since some writers don’t seem to understand how much, and what reasons, we, as an audience, allow characters to not just get away with, but how much of our sympathy remains with them. There are tons of instances where characters do something that is inexcusable to us and we end up not liking them. Now, with that having been said, let’s enter Pet Sematary.

Stephen King has stated that Pet Sematary is his scariest book, and I believe it is. I understand why many wouldn’t, since, when you go into horror, you expect it to be quite literal in that sense. You expect to be scared. But the novel’s horror comes from the human element.

They say when you have children, your life isn’t really your own anymore. And it’s true. You want nothing more than the best for your child, and if you yourself grew up in an environment that wasn’t the best, it’s more amplified. People don’t want their children to go through what they may have. It’s a powerful emotion. Love is powerful. We want to feel loved and want great things for those we love. Whenever someone we care about is going through a bad time, it affects us because we hate seeing them go through that. It is also important to remember you are always loved, and I know that there are instances where it’s hard to remember that. But as much as people make love into a great thing, it can also lead to various emotional offsets. Heartbreak and depression, jealousy and anger, and moments of irrationalness. It is this reason why we can’t call Louis stupid for attempting to bring his son back. This is an individual pushed by love and grief to do something that he knows will have severe consequences, but it is this same love that makes him irrational and blind enough to go through with it. This is how Pet Sematary may be King’s scariest novel. A powerful book reveals most of its power after you have finished reading it and mull it over. All of us at some point will come across someone, or multiple people, that will make you think about whether or not, given the opportunity to bring them back, you would do so. For better or worse. We have no right to sit and say; ‘no, because I’m not dumb,’ because we never know what our emotions would cause us to do.

But with all that said, things get muddier once Gage returns. Is it disrespectful to put it like that?

Gage returns, a demonic hellspawn shell of his former self, and ends up killing both Jud and his own mother before Louis can deal with him proper. This leads to one of my favourite endings ever, and, in my mind, Stephen King’s best. In a one-page epilogue, Louis is playing solitaire at the kitchen table, thinking it’ll be 'time soon'. The screen door is heard opening, a hand falls on his shoulder, and Rachel’s dirt-filled, gravelly voice says ‘darling.’ That’s it. It’s a gut punch of an ending.

Now, I understand film has to change the source material to fit the different medium, but the movie is one of the only examples off the top of my head that actually overshoots its mark. In the film, we actually see Rachel completely, the two go to embrace and kiss, freeze frame, followed by the sounds of Louis screaming.

As much as it turns the effectiveness of the novel’s ending into a conventional horror ending, it actually touches on what I believe to be the more interesting of talking points. Things involving Gage and loss and human emotion are obvious, but still worth discussion because it’s important, but it’s the ending that raises certain questions that make it worth more conversation than I usually see it get. You can say, with the loss of his son and wife, Louise is ‘dead’ himself, having suffered through two horrible losses in such short time.

But, the difference between Gage and Rachel is the fact that Louis has more to feel awful about in terms of the loss of Rachel, since he knows that he himself is directly responsible for her death. With the way he is presented in the ending, seemingly at peace and the way he talks about how it’s time soon, it makes you wonder if Louis brought Rachel back fully knowing that she was going to kill him, and that he deserves it, or even welcomes it, because he feels like he has nothing to live for…

Remember how I mentioned sometimes characters do things that make you dislike them, or just look at them negatively, and how the power of this book comes from the thinking points afterwards?

Louis, buddy… You have another child… you know, your daughter. Yeah, you might have forgotten I mentioned her, because at a certain point in the novel she is dropped off with family or friends. So, this begs the question throughout all of this; is Louis selfish in the end? Is his welcoming of death after these events, ones that obviously turned him into a shell of his former self, excusable? Or does the fact that he went through these things fall in line with being blinded by irrationality through devastation?

King has said that, besides being too bleak, the reason he isn’t a fan of the book is because it just, quote, “spirals down into darkness. It seems to be saying that nothing works and nothing is worth it, and I don’t really believe that.”

I understand why he would feel like that, but I think that it is this spiraling down into darkness that makes it work, because it very realistically, in a horror setting, shows just how far people can go.

Pet Sematary became famous once the movie was released for the line “sometimes, dead is better.” The dead, in horror, are frightening, but the lengths of what people would go to to reclaim what they lost if the hope or possibilities reared its head is more-so, especially since it can be so understandable. It is this connection that makes the novel not only one of Stephen King’s best, but possibly his most powerful.